Darlene Tate is newly married and newly pregnant, but a psychic has predicted that her fetus will expire at any moment.

Darlene Tate is newly married and newly pregnant, but a psychic has predicted that her fetus will expire at any moment.

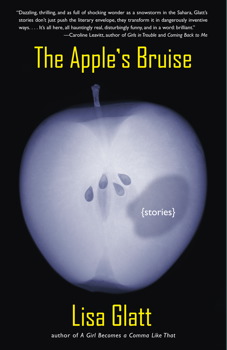

(from The Apple’s Bruise)

Now that I’m twenty-nine I’m becoming a new kind of woman, the kind who gets married to the guy who gets her pregnant, not the kind who keeps the pregnancy a secret and ends one when she discovers her boyfriend is cheating, and ends another when the gray-eyed tourist goes back to his home in Mexico, and ends the third when her boyfriend of nine weeks goes on a fishing trip with his buddies.

I read this story pretty soon after Glatt’s collection was published in 2005. I remember being impressed by these stories, not so much for the writing, but for their content. Glatt writes about women who get abortions and keep secrets from their husbands, women who manipulate others to get what they want. She writes about women who don’t want to be called “good girls,” all of which impressed me terribly at the time because I wasn’t finding stories like them. Coming back to this collection years later, however, leave me a little…what’s the right word? I guess I feel like they rely too heavily on these things. The writing doesn’t quite hold up for me in the same way.

Anyhow, I like this story pretty well. The beginning is especially nice, when Darlene asks her new husband, Jimmy, to make a list of all the things he doesn’t like about her. After some prodding, he does, and then he doesn’t want to stop. Darlene says, “Let me make a list for you,” to which Jimmy replies, “I don’t want a list.”

Worth reading, but there are so many women now writing these stories in much more thought-provoking and interesting ways. Check out some of it here.